In the concrete jungle of the Central Business District, a red flower-like structure stands out against the skyline.

Called a wind scoop, it perches atop the 40-storey CapitaGreen and its “petals” draw in cooler, cleaner air that is funnelled through the building’s air-conditioning system, helping to save energy on cooling.

It is among the energy-saving features introduced in buildings in recent years, with the Building and Construction Authority (BCA) aiming for 80 per cent of buildings in Singapore to be green by 2030.

Cooling systems are a big drain on power, taking up 40 per cent to 50 per cent of a building’s energy consumption. Together with other energy-saving features, such as a double-skin facade to reduce heat gain, the wind scoop helps CapitaGreen generate monthly savings of about 580,000kwh – equivalent to the energy needed to power about 1,500 four-room Housing Board flats in a month.

The premium Grade A office development by CapitaLand sits on the site that used to house Market Street Car Park and was completed in late 2014.

In one-north, near Buona Vista, sits Galaxis, an integrated development by Ascendas-Singbridge designed to generate 30 per cent more energy savings compared with other buildings.

“This translates to estimated energy and water consumption savings of $900,000 per annum,” said Mr Jeffrey Chua, chief executive of Ascendas-Singbridge Services.

Together with other energy-saving features, such as a double-skin facade to reduce heat gain, the wind scoop helps CapitaGreen generate monthly savings of about 580,000kwh – equivalent to the energy needed to power about 1,500 four-room Housing Board flats in a month.

The building, which consists of a 17-storey business park tower, a two-storey retail podium and a five-storey office block, was completed in late 2014.

Mr Chua said the high efficiency of the air-conditioning system contributes to about two-thirds of the savings. For instance, the pipes and equipment are laid out such that the recirculation of air is reduced.

To maximise energy savings, the developer set up the Ascendas-Singbridge Operations Control Centre in 2017. It monitors the performance of 26 buildings, including Galaxis.

The centre uses data and video analytics to reduce operational downtime and enhance security through early detection and response to incidents and faults. It also monitors toilet use to determine the timing and frequency of cleaning.

It is among the first of such centres here. In February last year, statutory board JTC launched its $15 million J-Ops Command Centre in Jurong Town Hall Road. The centre oversees the facilities of more than 20 JTC buildings.

However, the latest technology is not always limited to gleaming skyscrapers.

One would not expect to find state-of-the-art technology at Joo Chiat Complex, a shopping mall built in 1982 that is known for its textile shops.

However, in 2015, the building underwent a two-year retrofitting process led by energy service company Johnson Controls.

Mr Derek Teo, leader of special verticals and key account management at the company, said: “The building is old, but the underlying chiller technology is one of the latest.

“The retrofitting opens up doors to innovative solutions, such as connecting (the chiller system) to the ‘cloud’, which can help the old building to be connected in a smart digital way.”

If the chiller system is connected to a cloud server, anomalies may be detected before breakdowns, potentially reducing mean repair time by 60 per cent, said Johnson Controls.

Since the chiller plant started running in 2017, close to 1.2 million kwh has been saved, which has helped save $250,000 in utility costs. The amount of energy translates to 503 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions – equivalent to the emissions produced by the electrical consumption of 125 four-room flats in the same time.

Carbon dioxide is among the greenhouse gases that pollute the environment and contribute to global warming.

In 2017, Joo Chiat Complex won the Green Mark Platinum award, one of the most prestigious accolades for green buildings given by the BCA.

It is crucial that old buildings like Joo Chiat Complex meet green standards. Currently, only about 40 per cent of existing buildings are green.

Besides developers, there are also firms, such as Barghest Building Performance (BBP), which provide energy-saving solutions.

Using optimisation algorithms to improve the efficiency of installed equipment, its team of 40 engineers aims to shave energy use in 26 sites across eight markets, including Singapore.

BBP chief executive Poyan Rajamand said it has seen millions of dollars in annual savings for customers, which include tech giant HP and Resorts World Sentosa.

The firm, which was started in 2012, is now working on using wireless sensors to improve monitoring of parameters such as temperature, humidity and water pressure.

Mr Rajamand pointed to the increasing trend of Singapore energy-saving companies going overseas to share their knowledge.

“It’s becoming an export industry,” he said. “Singapore companies have a competitive advantage because the authorities here have been driving energy efficiency for decades.”

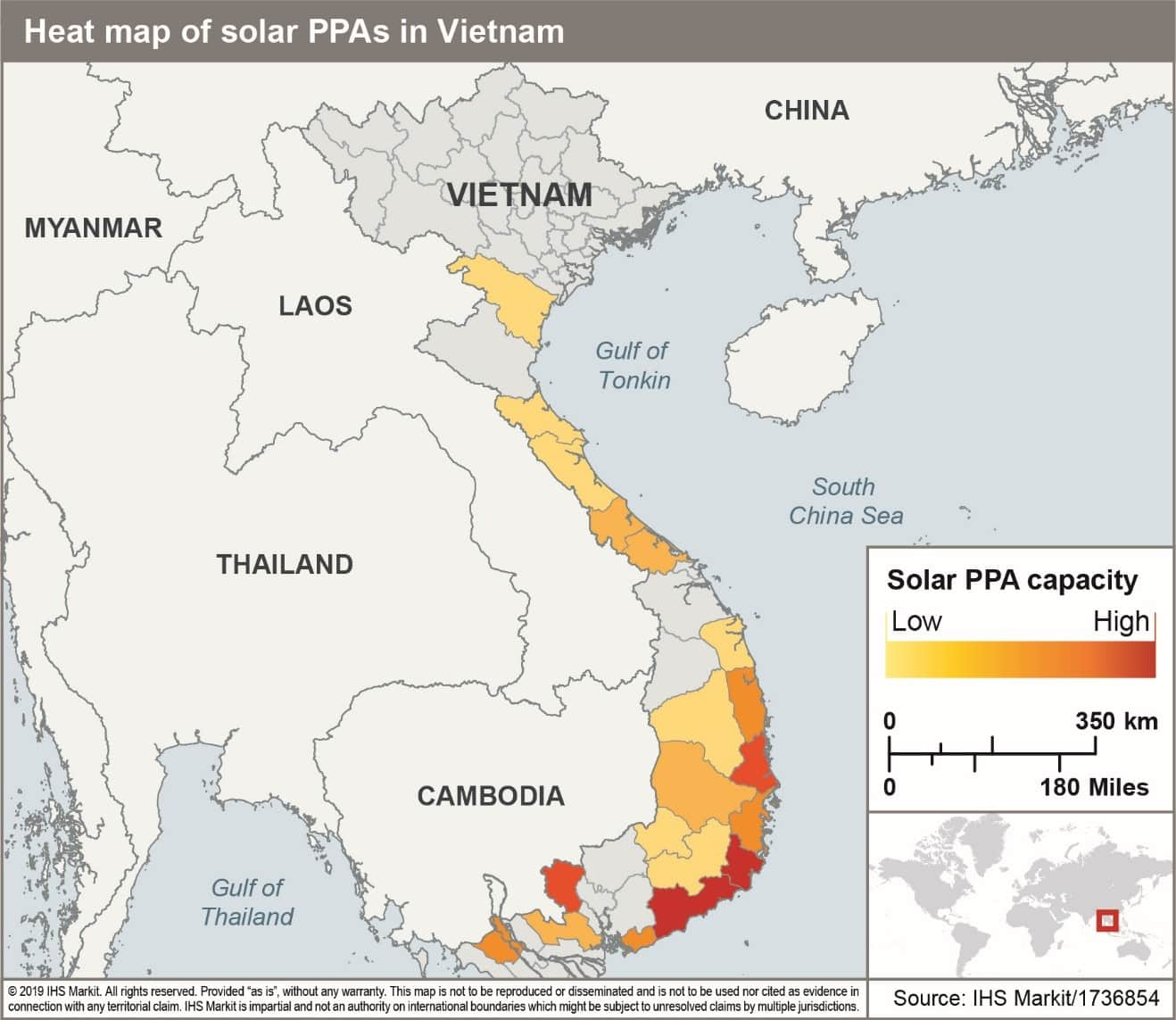

Figure 1: Heat map of solar PPAs in Vietnam

Figure 1: Heat map of solar PPAs in Vietnam