Myanmar’s launch of its first commercial solar plant last month is a step in the right direction for a country that has yet to provide more than half of its citizens with proper access to electricity.

Constructed on over 836 acres of land, an area equivalent to almost 530 football fields, the Minbu Solar Power Plant will be ASEAN’s largest solar power plant according to Thailand’s META Corporation – the project’s contractor and developer.

Although the project has been hailed as ground-breaking, there is still a long way to go before Myanmar achieves its goal of 100 percent electrification by 2030.

Supply and demand

The power plant will have a total capacity of 170 megawatts (MW) and is capable of producing 350 million kilowatt hours (kWh) annually, electrifying about 210,000 households. Constructed in four stages, the completion of the plant’s first stage now allows it to produce up to 40 MW of electricity.

The next two stages will add 40 MW each while the fourth and final stage will add 50 MW.

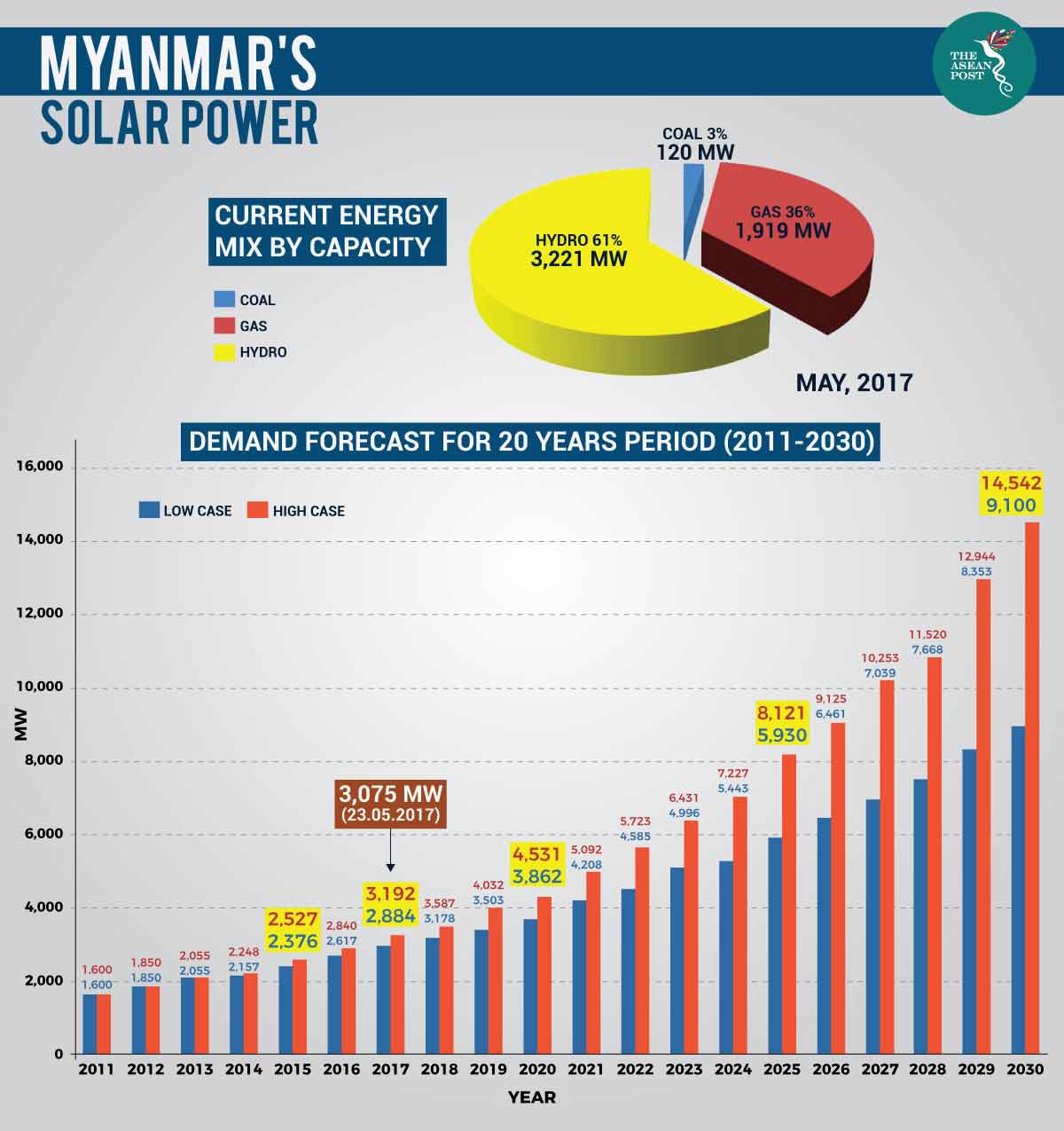

With Myanmar media reporting that the country produces between 2.9 gigawatts (GW) and 3.1 GW of electricity – which is just enough for 44 percent of the country’s population of 55 million people – the 170 MW that the Minbu Solar Power Plant will be capable of generating can only contribute to less than 0.5 percent of the nation’s current power demand.

According to recent estimates by the World Bank, energy consumption will grow at an average annual rate of 11 percent until 2030. In a report published last month titled ‘Myanmar Economic Monitor: Building Reform Momentum’, the World Bank predicted that peak demand is expected to reach 8.6 GW by 2025 and 12.6 GW by 2030, which is a significant increase from current levels.

Tellingly, the World Bank notes that Myanmar needs to invest twice as much – up to US$2 billion annually – and implement projects three times faster if it is to address its rapidly growing electricity demand.

Myanmar’s economic growth is expected to rise to 6.5 percent in the 2018-19 fiscal year due to strong performance in its industrial and services sectors – and the lack of electricity is a huge turn-off for any investor.

“Only when the government can fulfil the electricity requirements can it practically invite foreign investors,” said Gevorg Sargsyan, the head of the World Bank’s Myanmar Office.

As it is, Yangon – the largest city and former capital – consumes half of the nation’s power supply, with the rolling blackouts throughout the country painting a bleak picture of the immense challenges facing Myanmar’s power sector

Why solar?

While the government has plans to use liquefied natural gas (LNG) to increase its electricity generation to 6 GW, nearly double the current supply, LNG is an expensive investment and one that takes much longer than solar to get off the ground.

The country’s energy needs are largely met through hydropower, but its environmental, geopolitical and social costs are now growing concerns for the average Myanmar citizen.

Dams also take longer to construct than LNG plants, and the fact that water levels in the Mekong River are at its lowest in a century – partly due to climate change and regulated flow at upstream dams – also point towards solar as being the most cost-effective and reliable source of power for Myanmar.

Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi praised solar power for its low maintenance costs, reduced emission levels and contribution to the nation’s technological development during the Minbu Solar Power Plant’s opening ceremony. While solar energy has its disadvantages – its dependence on sufficient irradiance, large land areas and expensive batteries – it seems like the most promising option for Myanmar.

A lot of research has been done on the country’s potential to generate power through solar, with the International Growth Centre (IGC) – an economic research centre based at the London School of Economics – estimating in 2016 that Myanmar’s solar potential could be 51.9 terawatts (TW) per year. 1 TW is equivalent to 1,000 GW.

“Myanmar has an incredible potential for solar energy, but the government still has a lot of work to do to unleash the potential and to attract foreign direct investments into Myanmar´s solar industry,” noted Stefano Mantellassi, Chair of the SolarPower Europe Emerging Markets Taskforce.

“Rising electricity demand, rapid demographic growth and strong neighbour solar countries like China, India, and Thailand give Myanmar great opportunities to increase the installed solar capacity.”