BANGKOK — It wasn’t a flood. It was a tsunami, Premrudee Daorung said of the wall of water that tore through the forests of Laos’ Attapeu province, snapping timber like matchsticks and flattening entire villages.

The July collapse of the Xe-Pian Xe-Namnoy saddle dam in southern Laos and the widespread disaster that followed made international headlines. But Premrudee, coordinator of the Lao Dam Investment Monitor — along with several other development and water experts — says many other mega-hydropower projects in Laos are little more than quiet, slow-moving disasters.

Shortly after the Xe-Pian Xe-Namnoy collapse displaced thousands and claimed at least 40 lives, the Mekong River Commission called the dam break a national tragedy, but also an opportunity. It’s one that “ushers in new hope for a more optimal, sustainable, and less contentious path for development of one of the greatest rivers in the world,” MRC CEO Pham Tuan Phan said in a statement at the time.

The Laos government announced a halt to proposed dams while it reviewed existing hydropower facilities in a move that pleased watchdogs. But just one day later, it initiated prior consultations on the controversial Pak Lay dam in northwestern Laos. The collapse may have triggered international sympathy, but it wasn’t enough to shatter the idea that hydropower should be a pillar of sustainable development along the Mekong — a farce that the World Bank has spent nearly two decades promoting, according to Bruce Shoemaker, an independent researcher focused on development issues in the Mekong region.

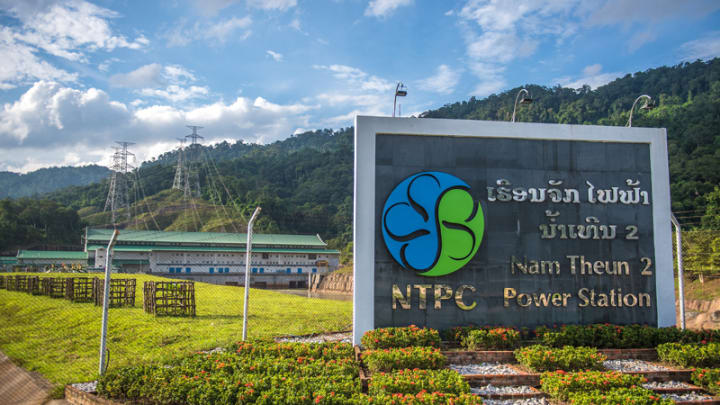

In December 2017, the World Bank handed over the Nam Theun 2, a $1.3 billion dam partly financed by the Asian Development Bank, to the Laos government. The mega-project was positioned as the future of sustainable hydropower, said Shoemaker, who began following the project long before its approval in 2005. Instead, in a bid to become a socially and environmentally responsible “model dam,” NT2 failed communities, the environment, and continues to threaten local livelihoods, critics say.

A ‘model’ dam

Plans for NT2 can be traced back to the early 2000s, when, Shoemaker said, the World Bank began touting the concept of hydropower as one of dual purpose: To make the country richer while contributing to poverty alleviation and conservation efforts. But the community benefits attached to the mega-dam were doomed from the start, experts who have researched the project told Devex.

When NT2 got the green light, several NGOs signed on to help relocate 6,000 people to the southern edge of the new reservoir site, beside an area identified for community forestry practices. The dam was operational by 2010, with 90 percent of the power exported to Thailand. But by 2012, progress reports regarding livelihoods and conservation efforts from bank-appointed external panel of experts were souring, said Shoemaker, who is co-editor of recent book “Dead in the Water: Global Lessons from the World Bank’s Model Hydropower Project in Laos.”

It wasn’t surprising to Glenn Hunt, who previously worked in the region and conducted an early assessment of the project’s social development plan. Community forestry is something that has never worked in Laos, he said, and this experiment was no different: “For one of the pillars that was supposed to be the primary source of income, it’s been an unmitigated disaster.”

The reservoir flooded farmland, meaning much of the community’s livestock soon starved and people could no longer count on their crops for income. The association set up to manage the forest largely fell apart, the sawmill will soon be closed, and the effort has not provided the third of villagers’ income it was meant to, Hunt said.

Residents were relocated to new houses, which are accessible via new roads, and the World Bank celebrated the new clinics, toilets, electricity, and water pumps in its statement declaring the closure of the project in December 2017. It’s the tradeoffs for the infrastructure that are problematic, said Niwat Roykaew, head of the Thai people’s network Rak Chian Khong Group.

“If you have the house, you have the house. But what to eat? How do you feed your family?” Niwat said.

Reservoir fisheries have proven to be the most sustainable pillar, though it’s been difficult to keep those outside the immediate community from fishing as well. But with an absence of other income-generating opportunities, community members are instead using the reservoir to access nearby protected land — an area that hosts several threatened species and was meant to benefit from funding and additional oversight — to poach animals and valuable rosewood.

Downstream, villagers have reported a drop in wild fish catch and loss of riverbank gardens. Shoemaker, who had conducted a livelihoods study of the community along the Xe-Bang Fai river in 2001, returned in 2014 to find that the fish market had dwindled, and low-lying rice fields had flooded.

The impact of NT2 is strikingly similar to the World Bank-financed Pak Mun dam, completed in 1994 in Thailand’s Ubon Ratchathani Province, said Kanokwan Manorum, a professor at Ubon Ratchathani University who has researched water and land governance in the area for 20 years. There, resettled villagers faced comparable losses, and turned to broom making after fish catch declined.

“The mistakes we face about the Pak Mun dam are already repeated in the Xe-Bang Fai area,” Kanokwan said. “It shouldn’t be like that. The World Bank should have learned about the impacts of the Pak Mun dam, and should make a better dam. I feel like the better dam will never happen.”

After several emails, World Bank staff said they could not reply to questions regarding NT2 on short turnaround, but pointed Devex to the final report by an international environmental and social panel of experts, particularly this portion:

“The POE [Panel of Experts] has confidence that the project is on the road to overall sustainability. It is not there yet. The solemn additional undertakings by all stakeholders to maintain their support in the years ahead provide evidence of a renewed commitment to the ultimate goal of sustainability by all parties.”

The panel of experts had refused to sign off on the resettlement program in 2015, prompting a two-year extension. Now, as part of the final sign-off, the French development agency has taken over livelihood support for the next five years. Rather than evidence of renewed commitment, it’s proof that the project wasn’t sustainable, Shoemaker said.

Damming the Mekong

Laos is planning to build about 140 hydropower dams in its quest to become the “battery of Southeast Asia.” But Shoemaker and other water and development experts are urging the country to consider a different way forward.

“Investors position mega-dams as ‘high risk, high reward,’ Shoemaker said. “But who is taking the risks? The bank put in all these loan guarantees to the investors, but not for the people there.”

There is little room for communities to engage and advocate on these issues, especially against the nearly nonexistent civil society backdrop of Laos, where the majority of the dams in the region are planned. Lao Dam Investment Monitor’s Premrudee stated she was speaking on behalf of Laos villagers, who did not feel it was safe to speak themselves. The Xe-Pian Xe-Namnoy disaster has prompted global dialogue, and she is hopeful a review of the project will inspire change, she said.

But Hunt wants governments and developers to think further outside the box if they’re going to continue disrupting people’s lives to build massive dams: “Maybe the citizens need to be shareholders, or they need to be getting dividends from the company, something different. It’s their traditional land, why shouldn’t they be part-owners in the entire enterprise? That’s the type of thinking that needs to take place.”

Other suggestions revolve around considering alternatives to hydropower dams altogether. International Rivers, an advocacy group that has opposed the construction of mega-dams, is calling for participatory, Mekong basin-wide planning, and comprehensive options assessment, as well as financial and technical assistance to promote energy and development alternatives. No matter what, social and environmental risk must be costed into projects, said Maureen Harris, the NGO’s Southeast Asia program director.

NT2 and Xe-Pian Xe-Namnoy are just two examples that are now being heavily studied, Niwat, from the Thai Rak Chian Khong Group, said, but he worries about the hundreds of dams proposed along tributaries in the region undergoing less scrutiny.

Xe-Pian Xe-Namnoy is a “clear example” of how corruption and profit-driven investment can cause a disaster, he added, but he witnessed the slow-moving disaster caused by the NT2 project himself.

Niwat visited the plateau area that villagers called home before the dam construction. People living upstream or on the reservoir area had been told they could not build a new house or farm their rice paddies since the land would soon be flooded — and they would soon live in a nice new house elsewhere.

“The predam disaster was already there,” he said.