It’s tempting to imagine hydropower as a relatively modern phenomenon – born in the 1950s and really taking root only in the 21st century.

Yet, that would ignore the fact that humans have been harnessing the power of water for well over 2,000 years, ever since the ancient Greeks used running streams to move wheels for the purposes of grinding grain.

Fast-forward two millenniums and it has become one of the most efficient and cost-effective ways of generating electricity.

The world still has a long way to go before realising the dream of universal, clean energy.

Bob Dudley, BP’s group chief executive, said in the company’s Statistical Review of World Energy Report 2019 that although renewable energy is growing far more rapidly than any other form of power, it still supplies only a third of the required increase in power generation – about the same amount as coal.

Governments increasingly recognise hydropower as playing a vital role in national strategies for delivering affordable and clean energy, managing fresh water, combating climate change and improving livelihoods

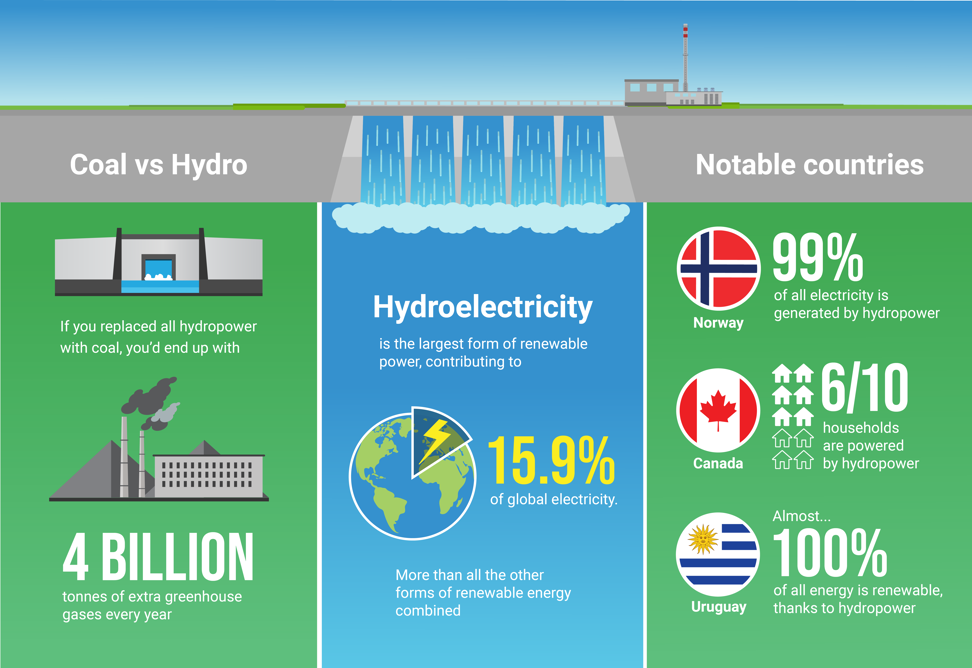

Of that renewable energy, it’s often sources such as solar power that generate the most headlines. But the truth is that hydroelectricity is the world’s largest form of renewable power, contributing to 15.9 per cent of global electricity – more than the combined contribution of all other forms of renewable energy.

Put another way, if the energy generated by hydropower was replaced by coal, it would result in an extra 4 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases every year.

Hydropower’s increased importance to the global energy grid comes at an important juncture in human history; the UN’s 2015 Paris Accords and Sustainable Development Goals both highlighted how imperative it is for the world to move from fossil fuels to sustainable sources of energy to minimise the rise of global temperatures and cut mankind’s impact on the planet and its climate.

This clarion call has been heard around the world. In Norway, 99 per cent of all electricity is generated by hydropower, while in Canada, six out of every 10 homes are powered by hydroelectricity, which has also created thousands of jobs in the country.

Uruguay has reached almost 100 per cent renewable energy, thanks largely to hydropower.

Asia wakes up to hydropower

However, it’s in Asia where hydropower’s potential is truly being unleashed.

China, with 352 gigawatts in 2018, is the world leader in terms of installed capacity – far ahead of second and third-placed Brazil and the US, which both have just over 100GW of installed capacity.

Other Asian nations such as Japan, India and Vietnam also rank among the top nations in the world for hydropower capacity.

“Four years on since the Sustainable Development Goals were agreed at the United Nations in 2015, governments increasingly recognise hydropower as playing a vital role in national strategies for delivering affordable and clean energy, managing fresh water, combating climate change and improving livelihoods,” Richard Taylor and Ken Adams, the International Hydropower Association’s chief executive and president, respectively, said in the Hydropower Status Report 2019.

“Hydropower development today is most active in fast-growing economies and emerging markets, with the East Asia and the Pacific region, followed by South America, adding the highest additional capacity last year.”

Overall, Asia alone accounted for 42 per cent – or 543GW – of the world’s total installed capacity of 1,295GW last year.

World’s largest hydropower plant

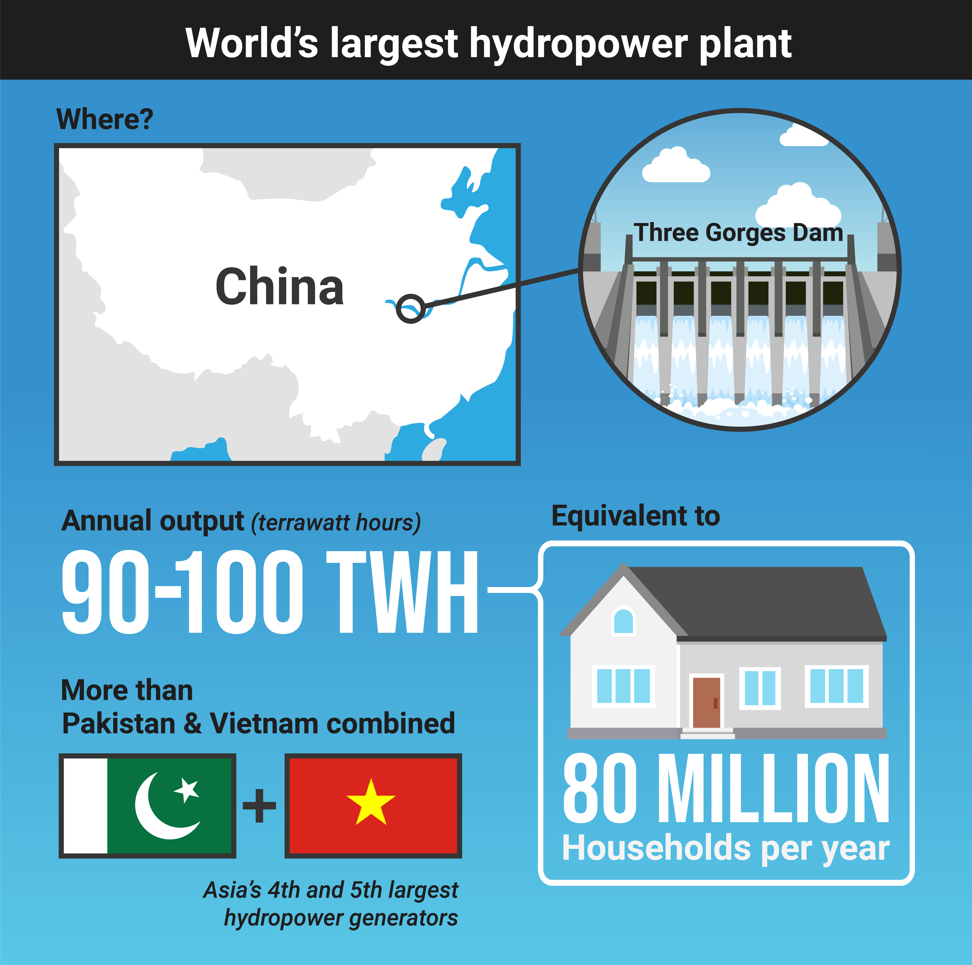

Asia is also home to the world’s largest hydropower plant, China’s Three Gorges Dam – which spans the middle reaches of the Yangtze River in Yichang, Hubei province – which produces 90 to 100 terawatt hours (TWH) per year – enough energy to power 80 million households.

The power generated by this one dam is more than the overall capacity of Pakistan and Vietnam, Asia’s fourth and fifth-largest generators of hydropower.

Hydropower development today is most active in fast-growing economies and emerging markets, with the East Asia and the Pacific region, followed by South America, adding the highest additional capacity in 2018

Vietnam has been leading the charge in Southeast Asia, a region which has more than doubled its hydropower capacity, from 16GW to 44GW, between 2000 and 2016.

Laos, Vietnam’s landlocked and impoverished neighbour, has a theoretical potential of 18,000 megawatts of hydropower and intends to double the 46 operating hydroelectric plants it has by next year.

Hydropower is essential to the country’s economy, accounting for 30 per cent of Laos’ exports and earning it the moniker “The Battery of Southeast Asia”.

On the whole, the availability of hydropower is a boon to Asia and the Pacific, which is home to more than 4.4 billion people who account for more than half the world’s energy consumption – 85 per cent of which is in the form of fossil fuels.

While industrialisation and urbanisation is growing at a rapid pace, the reality is that more than 10 per cent of this area’s huge population still lacks access to electricity – a clear hindrance to the region being able to improve the incomes and lives of its residents.

With affordability a core concern, hydropower makes even more sense because it is one of the cheapest energy sources available today.