- Oil & Gas

–

- Indonesia

A Repsol-led consortium of businesses has announced a major gas find in Sumatra, Indonesia.

The prospect was estimated to hold in the region of over 250 million barrels of oil equivalent.

Indonesia’s upstream regulator SKK Migas confirmed a gas discovery at the Repsol-operated Sakakemang PSC onshore Central Sumatra, Indonesia last night.

Wood Mackenzie’s research director Andrew Harwood said of the find:

“Repsol’s Kali Berau Dalam-2 well re-entered after well control problems in late 2018, having targeted the Pre-Tertiary fractured basement play. Prior to drilling, the prospect was estimated to hold in the region of 1.5 tcf of gas, or over 250 million barrels of oil equivalent.

“Further appraisal will be required to determine the extent of the discovery and firm up resource estimates, with another well scheduled on the block for later this year. Wood Mackenzie estimates anything larger than 300 bcf would be considered commercial, given proximity to gas infrastructure.

“The discovery is just 25 kilometres from the Grissik gas plant, which gathers and processes production primarily from ConocoPhilips-operated Corridor PSC, before sending it to buyers in Sumatra, West Java and Singapore.

“Besides operator Repsol which holds a 45% stake in the discovery, the news is very encouraging for the other PSC partners, including PETRONAS, which farmed into the block for 45% in January 2019, and MOECO which holds 10%. ConocoPhillips and PERTAMINA will also be interested in the result, as they look for resource that could extend the life of the Corridor PSC, scheduled to expire in 2023. The Corridor PSC is a key supplier of gas to Singapore and West Java, but is expected to see declining output from 2024 – a new source of supply would also be positive news for gas buyers in these markets.

“Indonesia’s oil and gas regulator, SKK Migas, has recently upped its efforts to encourage exploration in the country as it faces dwindling output and a lack of new investment activity. The regulator has targeted the discovery of at least one new giant field (500 million barrels of oil or equivalent) by 2023. The Kali Berau Dalam discovery could be the good news Indonesia needs to kick-start its exploration sector.

“If pre-drill estimates are realised, it would be the largest discovery in Indonesia since ExxonMobil’s Cepu discovery in 2001.”

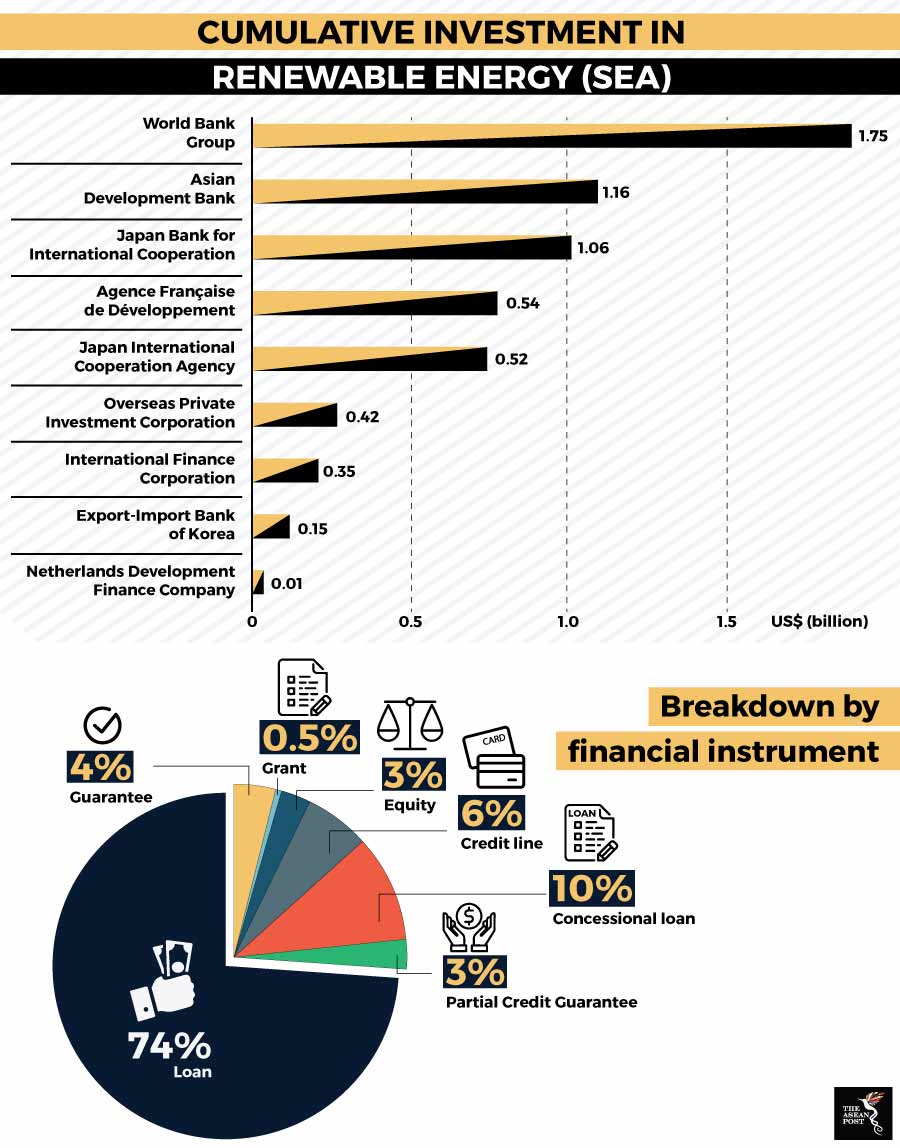

Source: International Renewable Energy Agency

Source: International Renewable Energy Agency