Yet, power continues to be in short supply. The government is now rushing five so-called “emergency power” projects totalling more than 1000 megawatts with Chinese companies in order to avoid repeating this year’s widespread blackouts and scheduled outages, which interfered with business operations and reduced productivity levels.

In the meantime, the higher tariffs appear to be strangling Myanmar’s economy. Despite individual measures to reduce power consumption, local business owners and residents told Myanmar Times they have struggled to remain profitable due to the rate increase.

The electricity bill of The Best Premier tea house in Kyauktada township, Yangon, has more than doubled from K90,000 to as high as K180,000.

“If the increase in electrification rates isn’t accompanied by a stable supply of energy, then the hike is meaningless,” said Ko Kyaw Htike Oo, who owns The Best Premier .

Eleven local teashops, restaurants and hair salons surveyed now either seek to reduce power consumption to offset the increased rates, or raise their revenues by charging consumers more.

“As soon as I knew about the tariff hike, I considered increasing the price for some food items,” KO Kyaw Htike Oo said, noting the impact on his business by the tariff hike.

Now he sells Myanmar tea at K500, a 25 percent increase from the original price K400. Even after adjusting the price, profit fell by more than K100,000 a month.

The energy ministry in July raised the electricity rates substantially, the first changes in the tariffs in five years.

Under the new rates, residential households and religious buildings will continue to pay at the previous rate at K35 per unit, but only for up to 30 units. For consumers using more than 30 units of electricity now, the government has introduced further breakdown pricing. Consumers and businesses can pay from 1.3 times to 2.5 times more – up to 72.9pc of increase.

‘Now I use charcoal more than a hot plate to heat food, so it’s definitely more work for me.’ – Ma Htwe Htwe Tun, Stall owner

Consumption trends

The increased tariff has raised awareness among the public about using electricity, prompting them to alter their consumption patterns. Electricity consumption for households has mostly decreased after the tariff hike among the households Myanmar Times talked to.

“We have limited our usage of the hot plate,” said Ma Htwe Htwe Tun, who runs a street food stall on 39th Street. “Now I use charcoal more than the hot plate to reheat the food, so it’s definitely more work for me.”

Another teahouse owner in Kyauktada, Ko Thant Sin, took up drastic measures like turning off refrigerators at night.“Things have not been convenient after the hike,” Ko Thant Sin admitted. And problems arise corresponding to his counter-measures, such as meat being rotten easily, and the restaurant looked dimmer because of lights being turned off.

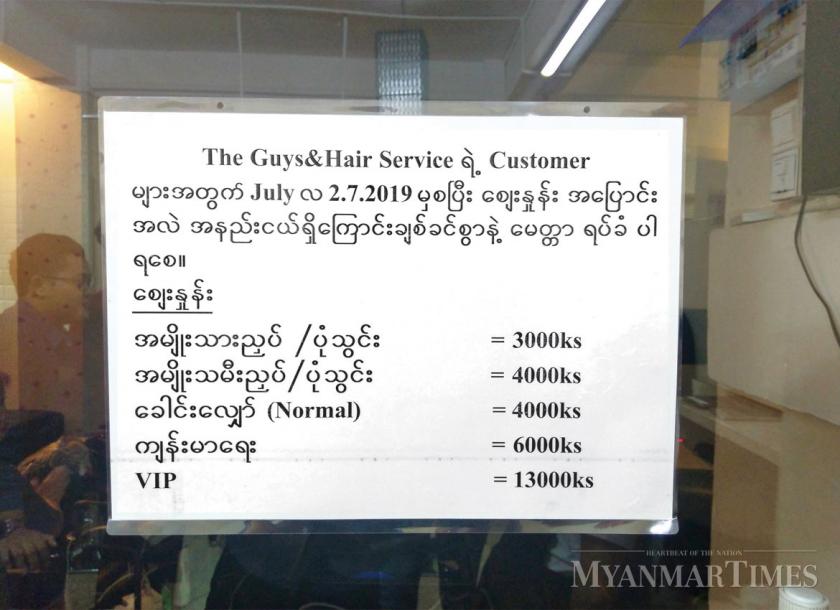

Ma Khin Myo Kyi from The Guys salon in downtown Yangon has limited options to reduce power consumption though. For salons, electricity is indispensable to most of the equipment, electric razors, hair curlers, and groomers, among others.

Nevertheless, the business owners said they have high hopes that the tariff hikes will result in stable power supply next year, which would help with some of their struggles.

Across the board, businesses have largely welcomed the hike in principle because they see that as the only way forward for electrification to take off, despite public sensitivity about the changes. Instead of running a deficit by heavily subsidising electricity supply, the government could channel the funds freed up into new power projects.

U Htet Aung Khine, government affairs manager of EuroCham Myanmar, said the tariff reform could help to narrow the gap between energy supply and demand, as long as the revenue generated by tariff adjustments leads to better power infrastructure.

“This move will not only attract more interest in the investment of power generation but will also create more attention in energy saving, efficiency, and power quality,” added U Htet Aung Khine

Persistent shortages

Considering that manufacturing businesses and factories consume most of the country’s energy, however, the power shortage in Myanmar is expected to continue, said Katie Patterson, editor of FMR Research & Advisory’s Myanmar Energy Monitor.

Ministry statistics suggest that power demand is growing by 15-17 pc every year. To fill the gap and provide the additional 12.6GW by 2030, at least US$2 billion per year of investments are needed, according to estimates by the World Bank.

Myanmar’s current power generation capacity is around 3600 MW but it was still 600 MW short of demand during this year’s hot season.

While the ministry’s permanent secretary U Tin Maung Oo said the five emergency projects are expected to ensure sufficient electricity for the summer of 2020, industry consultants are worried that the power supply will get worse significantly next year, even if the projects do materialise.

To tea shop owner Ko Kyaw Htike Oo, persistent power shortages coupled with higher tariffs could further disrupt his business and livelihood.

“We don’t know how the government will deal with the electricity distribution issue next summer, but if there are going to be power cuts, the situation will be bad for us.”

When asked about whether the government’s ability to deliver power supply would influence the way he votes in the 2020 elections, he said: “We will decide on who to vote as the election draws closer, and our vote will be based on the things we experienced and how we have suffered.”