Menu

The Heat Challenge in Southeast Asia

The problem of attaining thermal comfort has reached a critical point in the ASEAN region, where average daily temperatures routinely surpass 25°C and can rise to 35°C in urban areas. The ACE and UNESCAP Passive Cooling Study estimates that the region receives more than 1,500 cooling degree days each year, which is a substantial amount more than the global average. The urban heat island (UHI) effect, which can cause temperature differences of 7–10°C between highly populated urban areas and their rural counterparts, makes this thermal challenge much worse. These issues are most noticeable in rapidly expanding cities, where a lack of green space and a higher building density impede natural air circulation, increasing the need for efficient cooling solutions.

The immediate answer to this heat problem for the region’s approximately 67 million households is frequently to use air conditioning as their major source of indoor comfort. The intense heat outdoors is often forgotten as soon as cool air enters the room. Although this might seem like a simple fix, the unchecked use of air conditioners has serious hidden costs that are already influencing the future of the area and the world. These costs are both financial and environmental.

The need for cooling is expected to increase dramatically as Southeast Asia’s economy grows faster and temperatures continue to rise. In an effort to achieve thermal comfort, which is believed to improve well-being and productivity and, consequently, overall quality of life, more and more buildings are installing air conditioners.

According to the ASEAN Centre for Energy’s 8th ASEAN Energy Outlook, air conditioning alone is expected to consume over 29.7 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) of energy by 2050, or almost 40% of the energy required by the region’s commercial sector. As Southeast Asia continues to rely heavily on carbon-intensive energy generation, air conditioning systems’ emissions will exacerbate climate change-related issues, including rising temperatures. This leads to a paradoxical situation in which air conditioning, which aims to address the cooling crisis, instead makes the problems it is meant to address worse.

Given these difficulties, implementing passive cooling techniques through building certification offers a viable way to lower environmental impact and energy demand. The ASEAN area may move toward a more robust and energy-efficient future by emphasising sustainable architectural practices and improving building design, which would ultimately result in a healthier environment for its residents.

Cultural Heritage as Inspiration

Although it sounds like a recent breakthrough in the world of buildings and construction, the concept of passive cooling has always existed throughout various cultures around the world. In Southeast Asia, vernacular architectures are catered to the region’s relatively warmer and humid climate.

The Joglo house from Indonesia, for example, exemplifies passive cooling in its high ceilings and steeply pitched roofs that facilitate air circulation and reduce heat accumulation inside the house. Additionally, large overhangs and expansive verandas provide shade, significantly lowering direct solar heat gain and keeping the interior cool. Similarly, traditional houses in Thailand and Myanmar also feature high-sloped roofs and an elevated ground floor to optimise natural cooling and eventually reduce indoor temperatures. This blend of cultural heritage and practical design strategies demonstrates that passive cooling is a time-tested strategy which should be incorporated in the modern design approach.

Despite its deep roots in local culture, passive cooling is still underutilised in modern Southeast Asian architecture. Although recent trends have brought sustainable designs forward, the affordability and convenience of air conditioning remain powerful incentives. The cost of retrofitting or modifying an existing structure with passive cooling modalities might also be too astronomical, making it difficult for those in low- or middle-income households to justify passive cooling implementation despite long-term savings. The scarcity of professionals with relevant expertise, as well as the inadequate regional supply of materials, will further impede the ubiquitous implementation of passive cooling.

The Role of Green Building Certifications

This is where green building certifications come into play. By establishing clear requirements, measurements and verification processes, certification enables organisations to confidently adopt passive cooling strategies while managing risks and ensuring desired outcomes. This provides a proven pathway toward reducing environmental impact and energy demand through sustainable building practices

Across Southeast Asia, governments and green building institutions have promoted energy efficiency and sustainable building practices through various certification programs. Green building certifications, such as Indonesia’s Greenship and Green Buildings, Malaysia’s Green Building Index (GBI) and GreenRE, Philippines’ Building for Ecologically Responsive Design Excellence (BERDE), Singapore’s Green Mark, Thai’s Rating of Energy and Environmental (TREES), and Vietnam’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design On a Sustainable Urban System (LOTUS) provide clear standards and play a pivotal role in raising awareness among architects, contractors, developers, and policymakers about the gravity of implementing sustainable practices in buildings, including passive cooling.

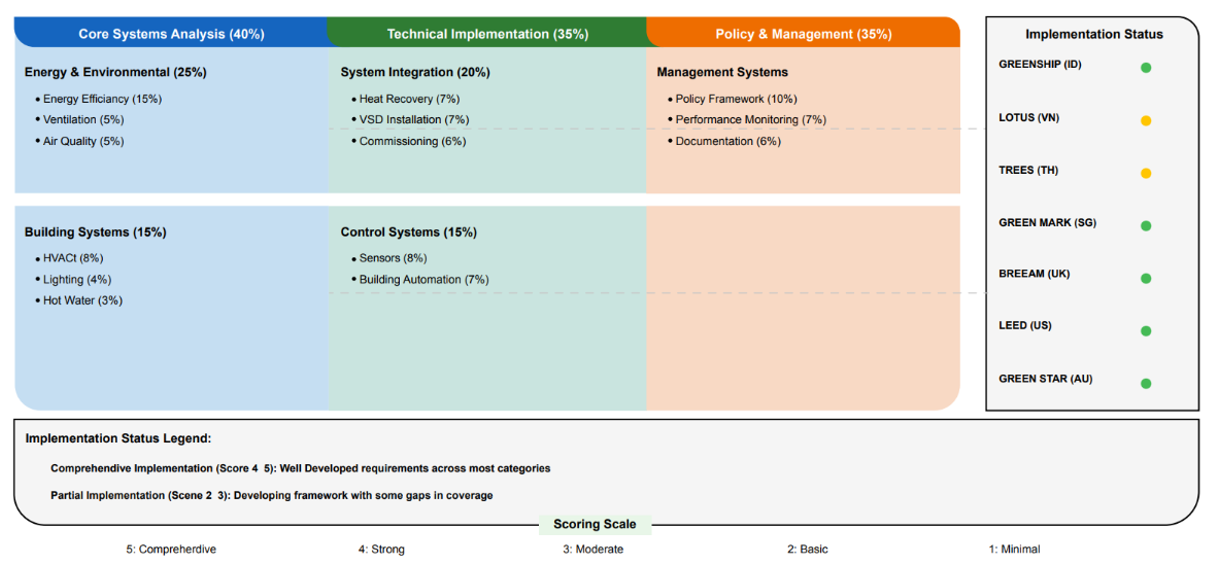

Figure 1. Comparison of Green Building Certification

A comparison table (see image above) of the certifications used in several ASEAN Member States and international standards reveals differences in how each system prioritises aspects like air conditioning efficiency, ventilation, and lighting systems. Singapore’s Green Mark, Vietnam’s LOTUS, and Thailand’s TREES certification advocate for a blend of natural ventilation and mechanical ventilation as necessary. This adaptability ensures that buildings can maintain indoor comfort even in densely populated urban areas, where air circulation is often hindered by closely packed structures.

In Indonesia, the Greenship certification places a strong focus on building envelope systems and policies for energy use reduction, both critical components of sustainability’s headway in the built environment. By setting clear criteria for energy management policies and requiring minimum energy efficiency benchmarks, Greenship ensures that new buildings are constructed with sustainability, which includes passive cooling, as a fundamental principle.

International certifications like the UK’s BREEAM, USA’s LEED, and Australia’s Green Star give insights into global standards. While these international certifications may not be tailored to tropical climates, they set valuable benchmarks that influence certifications in Southeast Asia, encouraging a global shift towards sustainable cooling. The increasing adoption of international certifications demonstrates their effectiveness in driving sustainable building practices, including passive cooling, across diverse markets and building typologies in the region.

Aside from being a promotional tool, green building certifications also provide exemplary applications of passive cooling in modern architecture. For instance, CapitaGreen, a recipient of Singapore’s Green Mark Platinum Award in 2012 and recognised in the ASEAN Energy Awards 2023 as one of the best practices in energy-efficient building, illustrates the effectiveness of passive cooling in densely built urban environments. This building gives a stellar example of passive cooling implementation with its vegetated, double-skin facade and a cooling system that relies on fresh air intake through the building’s one-of-a-kind inner-duct construction. Meanwhile, in Malaysia, the GBI Platinum Award 2021 was bestowed upon the University of Technology Sarawak for its incorporation of natural cross ventilation, low-emissivity glass building facade, and a large outdoor plaza as a circulation space to provide an ideal indoor thermal sensation suitable for academic activities. These certified buildings demonstrate how passive cooling is achievable and valuable in modern settings.

Furthermore, green building certifications can enhance market value by rewarding buildings that incorporate passive cooling. These certifications can bring a competitive edge to the property. Achieving a green building certification not only signals environmental responsibility but also makes these buildings more attractive to environmentally conscious tenants and buyers, thereby promoting passive cooling as a desirable feature in new developments.

The Sustainable Way Forward

With the endless benefits of passive cooling, widespread adoption, unfortunately, still poses some problems. For certain developers, green building certifications may be seen as a low-return investment or a tertiary need, especially in less prosperous regions. Not to mention, there is a huge knowledge gap in numerous parts of Southeast Asia due to the lack of research, technology, and experts for passive cooling.

Nevertheless, the potential is immense. Opportunities for collaboration to establish a definitive step forward are on the horizon. The journey to making passive cooling a regional standard requires a commitment from all sectors: public, private, and educational. Southeast Asia’s climate may present unique challenges, but by embracing certifications that highlight passive cooling and working to expand the supply of eco-friendly materials plus local expertise, the region can lead a movement towards cooler, more sustainable urban spaces.

Recognising the weight of this discourse, the ASEAN Centre for Energy published a report, in collaboration with UN ESCAP, titled “Passive Cooling Strategies: Current Status and Drivers of Integration into Policy and Practice within ASEAN’s Building Sector“. This report explores the different modalities of passive cooling and how the implementation might look across regions in Southeast Asia. Furthermore, this report also covers the challenges of implementing passive cooling in Southeast Asia and all the prospective tools that can be used to smooth the process of its adaptation, e.g. green building certifications.

These certifications are not just labels. They represent a framework for building a future that respects the climate, honours cultural heritage, and meets the urgent need for sustainable living. As Southeast Asia grapples with the impacts of climate change, passive cooling presents a cooling solution that aligns with the environment, balancing comfort with responsibility.