Agriculture can either be the main cause or our greatest asset in fighting the climate crisis. But, for this, it must be radically transformed. Humanity now depends on just three crops (wheat, rice and maize) for more than half of its food. Our dependence on so few crops grown in so few countries to feed over seven billion people brings risks of food insecurity, political instability and environmental harm.

How we respond to this challenge will determine the fate of future generations and the planet. In the face of diminishing natural resources, more people and a hotter planet, our current food systems and the policies that govern them are unsustainable. The speed and extent of climate change are already overwhelming vulnerable communities and will soon affect those who are ill prepared for its consequences. The climate crisis means less suitable land and more hostile conditions for the crops on which we all now depend. At the same time, consumers increasingly demand nutritious food that is sustainably sourced and safe to eat. The days of cheap food imports based on calorie-rich staple crops grown in benign climates and transported along carbon-heavy supply chains are numbered. We need new options that are healthier for us and the planet. The most vulnerable countries are those who can’t feed themselves and have the lowest food reserves in the event of a global emergency as we are now witnessing in China. If we want to reduce the risks of political and economic disruption caused by food shortages, we need urgent and bold strategies and investment in `Next Generation’ agriculture that diversifies our food system beyond major staples grown as monocultures – somewhere else. We cannot rely on others to feed us.

First, we must use marginal land more wisely. In addition to land for agriculture and forests, there are vast areas within the ASEAN region that lie idle. Whilst these are too marginal for mainstream agriculture, they can support climate-resilient and nutritious crops that yield profits for farmers and healthy food for consumers. For example, bambara groundnut (kacang poi in Malaysia, kacang bogor in Indonesia) can produce protein-rich seeds in marginal soils across the region. With the richest reservoir of biodiversity on the planet outside Amazonia, the ASEAN region is literally sitting on a treasure trove of potential crops for the future. We ignore this huge comparative advantage at our peril.

Second, we must harness the potential of urban spaces for agriculture. The flight of rural populations to cities means that the ASEAN region is now predominantly urban, sedentary and, often, malnourished. Instead of crops grown faraway, we need to bring farming into urban spaces such as rooftops, gardens and communal areas. This means thinking about agriculture as a profession for city dwellers who can build agribusinesses from aquaculture, hydroponics, vertical farming and controlled environments that yield nutritious and high value products from diverse crops.

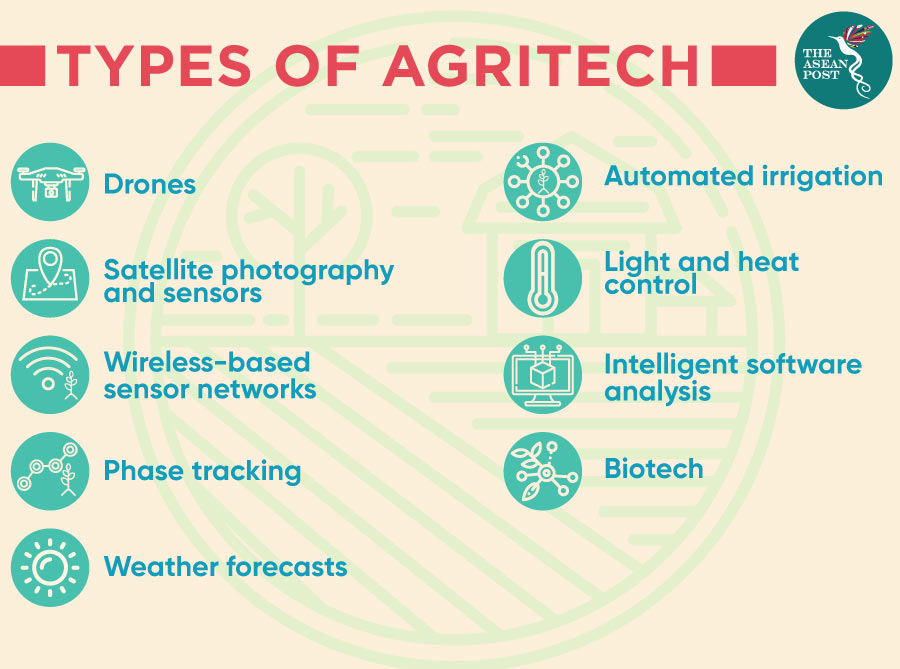

Third, we must encourage rural and urban youth to get into farming. More than half of ASEAN’s population is between 20 and 54, many have access to the Internet and most live in cities. Attracting urban, tech savvy, entrepreneurial young people into a career in agriculture is a huge opportunity and a major challenge. We will not meet this challenge in laboratories and lecture halls and through traditional approaches. Young ‘agripreneurs’ need real time access to digital technologies, expertise and mentoring to address specific situations. This requires a different kind of education that links new technologies, business skills and innovation with agricultural knowledge and research expertise.

How can we incentivise a new generation of agriculturalists with the resources and technologies to support economically viable use of rural and urban landscapes? The need is too urgent for top down directives, supply driven research and subsidies. Instead, we need to create an Agritech incubator that can access existing skills and facilities whilst adding innovations for next generation agriculture. Incremental improvements in the candle did not lead to the discovery of the light bulb. Incremental improvements in the existing model will not deliver an agrifood system that is fit for the future. We need a `light bulb’ moment for agriculture that links new technologies, young people and natural resources to transform agriculture – for good. It’s time to start.