Menu

Leaders from almost 200 countries worldwide came together in Glasgow, United Kingdom, to help advance concrete actions addressing the climate crisis.

After a one-year delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) commenced on 31 October to 12 November 2021 with the hope to secure global commitments in mitigation, adaptation, and finance.

Among the participants, leaders and delegates from ASEAN countries were present to negotiate and state their positions.

Road To COP26

In preparation for the COP26, ASEAN member states have released a joint statement that reaffirmed their commitments to tackling the climate emergency. Specifically, the information highlights the regional achievement of 21 percent energy intensity reduction in the energy sector, surpassing its aspirational target and 13.9 percent renewable energy share in the energy mix in 2018.

A different target, 32 percent energy intensity cutting by 2025, was set in the new ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation (APAEC 2016-2025 Phase II: 2021-2025). The region’s continuous effort to accelerate decarbonisation is low emissions.

The emissions status is demonstrated in each country’s nationally determined contributions (NDC). Despite experiencing the severe impact of COVID-19 and the climate-related disasters on the economy, and the fact that most ASEAN countries are not significant emitters of greenhouse gases (GHG), developing countries in the region have tried to undertake the highest possible ambition through their recently updated NDC.

Lao PDR committed to unconditionally reducing GHG emissions in 2030 by 60 percent compared to the business-as-usual scenario.

Malaysia, which previously committed to 35 percent emissions intensity reduction on an unqualified basis and further 10 percent upon receiving support from developed countries – now has raised its unconditional term to 45 percent and dropped its conditional clause.

Unlike its neighbours, Thailand did not change its emissions target in its updated NDC last year, but it has integrated the NDC targets into the National Strategy.

What Happened In Glasgow?

During the event, the ASEAN decision-makers expressed their contributions in different ways. Indonesia announced its new regulation that puts a price on emissions and mechanisms to trade carbon. The carbon emissions market should be enacted transparently and inclusively because the scheme should not be used for countries to buy their way out of lowering emissions. Singapore is also ahead in establishing a carbon tax and is very much involved in high-level talks to complete Article 6 of the Paris Rulebook related to carbon markets.

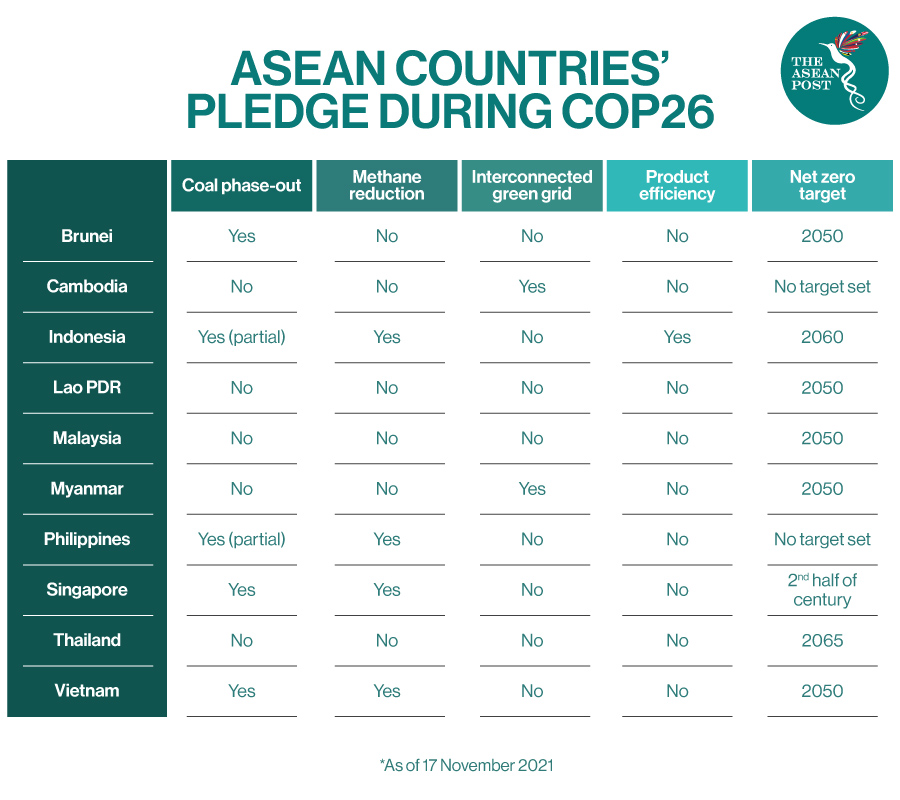

One of the imperative outcomes during COP26 was the Global Methane Pledge, which aims to cut 30 percent methane emissions collectively by 2030. Methane is the second-largest contributor to global warming after carbon dioxide and comes from agriculture and the fossil fuel industry. Over 100 signatories are joining this EU-US coalition, including Indonesia, one of the top-10 methane emitters. In addition, the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam are among the other ASEAN member states that signed this pact.

The Global Coal to Clean Power Transition Statement was another key agreement produced at the conference. More than 40 nations signed to this international effort to shift away from unabated coal power generation by 2040 or as soon as possible after that. The signatories include half of ASEAN, namely Brunei, Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam. Although Indonesia and the Philippines exclude the 3rd clause about stopping the issuance of the new unabated coal-fired power plants’ permits, it is still considered a bold move, considering that Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam are some of the biggest coal producers in Asia. The world’s leading coal-producing countries, such as China, the United States (US), and India, did not back this petition.

Several ASEAN governments are also seen supporting other energy-related initiatives, such as the One Sun Declaration and the Product Efficiency Call to Action.

Source: ASEAN Centre for Energy

Source: ASEAN Centre for EnergyPushing For Financial Support

The commitments made in NDC and COP26 could not be delivered without adequate finance.

Cambodia, for example, could only commit its NDC targets conditionally on international support to reduce emissions by 42 percent in 2030. The kingdom has identified the total required funding of US$5.8 billion for mitigation and another US$2 billion for adaptation.

The ASEAN joint statement on climate change also emphasised the guaranteed funding assistance of US$100 billion a year for 2020 until 2025 to developing countries, including several ASEAN nations. Financial resources are the top barrier in climate change mitigation, which is expected to be fully supported by developed countries.

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo echoed the call for urgent collective action on climate finance during his COP26 speech, “Indonesia will be able to contribute more quickly to the world’s net-zero emissions. The question is, how big is the contribution of developed countries to us?”

After heated discussions, nearly 200 nations adopted the Glasgow Climate Pact on 13 November, including phasing down unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. The good notions to combat the climate disaster we heard during COP26 should not remain as worthless words among policymakers.

The climate summit might be over, but there is a lot of homework to be done. Countries need to act and report those actions in next year’s COP27 in Egypt (short-term), realise their NDC targets by 2030 (mid-term) and reach net-zero emissions as soon as viable (long-term).

–

The original article can be found here.

Pic by Freepik.