Menu

In our last blog, we covered the chicken-and-egg situation of low-carbon hydrogen that ASEAN Member States (AMS) must break away from. Centre to the problem was how prevalent risks were in being the ultimate factor of a go/no-go decision in investing. In this article, we are going to dive deeper into the importance of risk in investing and explore what kind of derisking measures can be undertaken, along with the intricacies that eventually tag along.

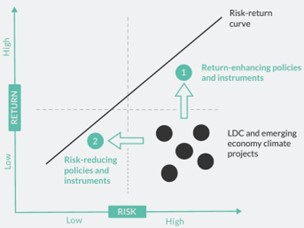

It is a foundational tenet in investing that high risk will yield high returns, however, climate investments such as clean energy—and by extension, low-carbon hydrogen—seem to not follow that pattern. They characteristically require substantial upfront capital investment, but the long-term returns are low despite being stable. Clean energy provides a social benefit that will be subject to price regulation by governments. Additionally, commercial investors have a shorter time horizon in expecting returns.

Figure 1. Risk-return profile of normal investments (positive gradient line) and climate investments (dots). Note that LDC stands for least developed countries. (GGGI, 2016)

To encourage more investments in clean energy, there should be measures to derisk, enhance returns, or even both. Uncertain demand could be derisked through demand creation, normally catalysed by Favourable offtake agreements guarantee demand at a fixed price, which ultimately provides confidence in revenue projections. Revenue generation can also be guaranteed through government compensation using a contract for difference (CfD)—precedented by wind project financing in Europe—in which power generators settle the difference between the electricity’s market price and the strike price set by a public entity. Contract for difference hence becomes a measure of both derisking and enhancing returns, as it tries to overcome the high price risk of low-carbon hydrogen and ensure a steady cash flow for the project.

In practice, implementing those measures is easier said than done. other than due to a significant price gap between conventional and low-carbon hydrogen, there is a risk aversion tendency for long-term agreements due to a lack of precedence in industrial uses and the transport sector. This paints a contrasting picture of VRE adoption in the power sector. Moreover, emerging markets and developing countries (EMDC) governments in general lack the fiscal freedom to provide similar compensation levels to low-carbon hydrogen projects compared to advanced economies. While raising short-term government revenues such as carbon tax in theory should work, that would not be easy to implement. It reminds us that it is important to translate these risk-return-improving measures into the local context, as implementing them in EMDCs would be faced with different challenges.

Perhaps a more well-known measure to both derisk and enhance returns is blended finance. Blended finance utilises both commercial and concessional loans to fund projects on the verge of commercial viability to attain enough profit so that they will be bankable enough to attract future commercial funding. The provision of concessional funds—which are grants offered in below-market terms such as domestic and global public and philanthropic funds—is critical for generating initial revenues and reducing the financial risk of revenue stability.

Despite Southeast Asia has been a recipient of numerous blended financing schemes, blended finance is not a silver bullet, as it only helps to derisk against financial risks, not eliminate non-financial risks. Many clean energy projects in EMDCs are not even on the ‘commercial verge’ as they contain multiple risks that eventually necessitate higher returns, and therefore, more concessional funds to incentivise inventors. In simple words, it is not the most strategic use of money.

Therefore, it is clear that the way forward is to control all the associated risks. This could be done by two broad derisking measures. Policy derisking is a measure to reduce risks associated with skill gaps, management of infrastructure assets, and legal and regulatory frameworks, through policy reforms. Meanwhile, financial derisking is a measure to transfer risk from private sectors to public actors, such as development banks. It includes guarantees, hedging, and future contracts, among others. While the option for compensating the risk is available, it is not viable for EMDCs like many AMS because, as mentioned, it necessitates a deep reserve of government revenues.

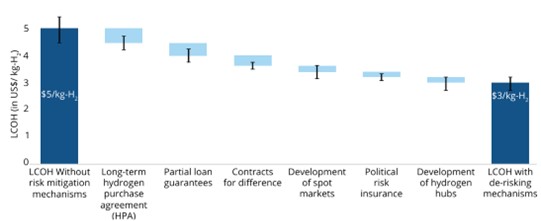

Figure 2. LCOH reduction if proper derisking measures are executed. (ESMAP, 2024)

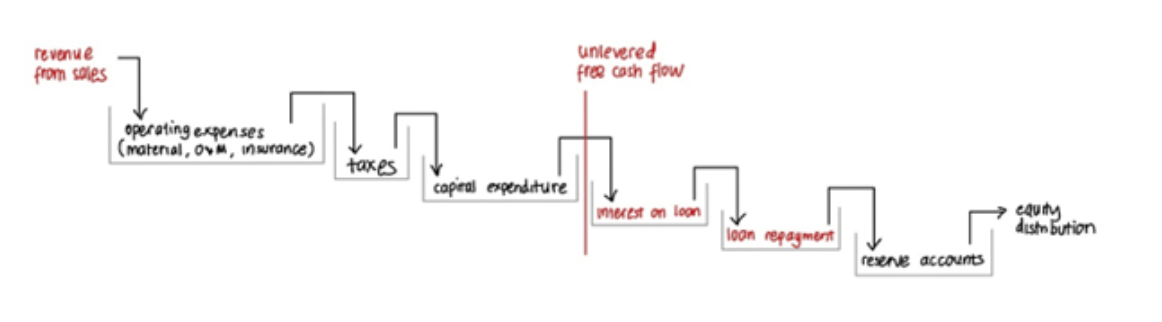

While there are various types of risk as illustrated in Figure 2, commercial lenders, particularly banks, are most concerned with default risk— the risk that borrowers may not meet their debt obligations on time. The likelihood of default risk depends largely on the availability of free cash flow—as illustrated in Figure 3, which refers to the cash a project has after accounting for operating costs and capital expenditures. This cash flow is used to repay loans and distribute dividends.

For lenders, the ability to forecast future revenues with confidence is essential, and this is where a key challenge arises: estimates indicate that low-carbon hydrogen demand is currently very limited. Most existing demand is concentrated in traditional sectors, where it is met by cheaper fossil-fuel-based hydrogen. This is the exact reason why banks tend to impose more conservative financial covenants—such as maintaining a certain D/E ratio—for projects with a higher perceived risk, like low-carbon hydrogen, which typically has a 6:4 D/E ratio.

Figure 3. Simplification of a typical cash flow waterfall.

(Adapted from the United States Department of Transportation)

The World Bank-led Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) estimated that these derisking measures in aggregate will generate tangible results in lowering the LCOH in EMDCs, as shown in Figure 5. AMS should take action promptly if they intend to drive down the LCOH value, following their carbon neutrality strategy to connect green infrastructure and markets. It should be remembered that there is a lag between our current choices on decarbonisation strategies to the time of economic impact (or perhaps consequence), hence no time should be wasted.